Behind government policies, recruitment figures and political pronouncements lies a quieter story—one of thousands of Junior School intern teachers living with anxiety, financial strain and professional uncertainty. While they are central to implementing Kenya’s Competency-Based Education (CBE) system, these educators say they are treated as dispensable labour, trapped in shifting policies and unclear timelines.

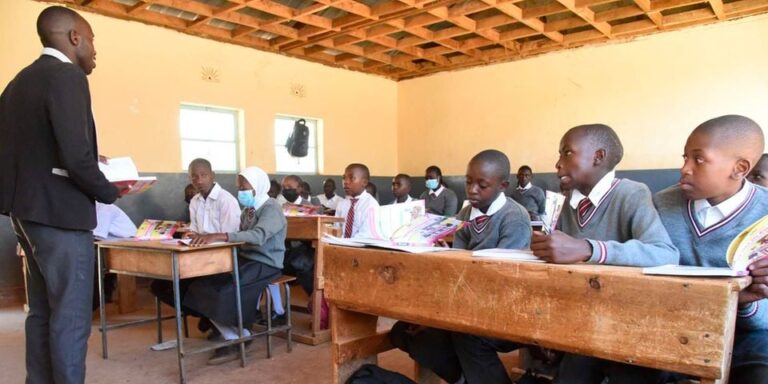

Intern teachers earn less than Sh18,000 after deductions, a salary many describe as unsustainable, especially given the rising cost of living. Yet they perform the full duties of regular teachers: lesson preparation, classroom instruction, learner assessment, discipline management, extracurricular supervision and school administrative work.

Many interns say they accepted the job believing it was a direct pathway to permanent and pensionable (PnP) terms. But conflicting statements from the Teachers Service Commission (TSC), the Ministry of Education, Treasury and even State House have eroded their trust.

For months, interns were hopeful after Treasury CS John Mbadi told Parliament that funds were already allocated to confirm all interns by January 2026. This calmed fears and gave hope for job security. However, Education CS Julius Ogamba contradicted this optimism just days later, warning that internships might be extended beyond 2025 unless more funds were released.

President William Ruto’s latest declaration—that interns will only transition after completing two full years—has now added to the emotional toll. Intern teachers approaching one year of service by December say they feel betrayed. They insist they joined under promises of earlier confirmation, not extended uncertainty.

The Kenya Junior School Teachers Association (KEJUSTA) has amplified these concerns, calling the internship model “inhumane” and threatening a fresh legal challenge. KEJUSTA chairperson James Odhiambo argues that interns are being exploited under the guise of workforce development. His message reflects a deep sense of frustration among educators.

The emotional toll is significant. Many interns report depression, stress and burnout due to overwhelming workloads and little support. Others say the uncertain career path affects their ability to plan families, pursue higher education or commit to long-term personal investments.

Teachers also note the difficulty of being fully responsible for learners while lacking job security. The weight of curriculum deadlines, competency assessments and behavioural management takes a toll when one’s employment future hangs in the balance.

For many, the issue is no longer just about money—it is about dignity, respect and professional recognition. They want consistent communication, clear policy direction and a genuine pathway to PnP employment that matches their commitment to CBE implementation.

Until the government resolves its internal contradictions and acknowledges the human cost behind its policies, interns will continue to feel undervalued, unheard and unsupported.