President William Ruto’s announcement that Junior School intern teachers will transition to permanent and pensionable (PnP) terms only after completing a mandatory two-year internship has reignited tensions within Kenya’s education sector. While the State House maintains that this directive is a structured staffing strategy under the Competency-Based Education (CBE) system, critics argue the policy now exposes deeper inconsistencies and growing institutional distrust.

The President, speaking at Kitui State Lodge, appeared keen to assure the more than 20,000 Junior School interns of eventual job security. However, instead of providing clarity, his remarks opened new conversations on labour rights, fiscal allocation, and government coherence.

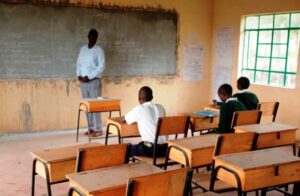

The two-year cap comes at a time when Junior School interns are increasingly vocal about exploitation, low pay, and unpredictable contract terms. Paid less than Sh18,000 after deductions, these teachers shoulder the full burden of lesson planning, assessments, classroom management, and extracurricular duties—yet without benefits or job security.

Teachers’ unions argue the internship model is effectively a government-backed structure of cheap labour. KEJUSTA, the main lobby, has accused the programme of being “inhumane,” citing a Labour Court ruling that flagged the model for violating labour standards.

The credibility of the government is further strained by conflicting official statements. Treasury Cabinet Secretary John Mbadi recently assured Parliament that funding had already been allocated to convert all interns to PnP by January 2026. But Education CS Julius Ogamba contradicted this, warning MPs that without additional funding, internships might be extended beyond 2025.

Such contradictions—now amplified by the President’s definitive directive—suggest internal misalignment and weakened sector planning. For the Teachers Service Commission (TSC), these remarks raise questions about its operational autonomy, as political pronouncements increasingly shape staffing decisions.

According to President Ruto, Kenya’s teacher shortage once stood at 110,000, and his administration will have hired nearly 100,000 by early next year. Yet TSC data paints a stark picture: Junior School alone faces a deficit of 72,000 teachers, with only 83,129 deployed so far.

Despite current plans to recruit an additional 24,000 interns by 2026, the deficit remains overwhelming. Critics fear the internship model only postpones the crisis while masking deeper structural problems such as insufficient budget allocation, planning lapses, and failure to prioritize CBE staffing needs.

President Ruto insists the model is pragmatic, arguing that more than 300,000 trained teachers are jobless. He described the internship plan as a “pathway” toward eventual absorption, assuring automatic confirmation after two years without negotiation.

However, teachers argue that as long as absorption is tied strictly to a two-year cycle and constrained budgets, thousands will remain stuck in limbo.

The government faces mounting pressure to harmonise its internal messaging, fund its commitments, and adopt a clear roadmap that protects labour rights while stabilising CBE implementation. Until then, the two-year rule remains one of the most controversial pillars of Kenya’s education reforms.